With the midterms wrapped up south of the border, American automotive aftermarket leaders are focusing on the next two years as pivotal in getting right to repair legislation in place.

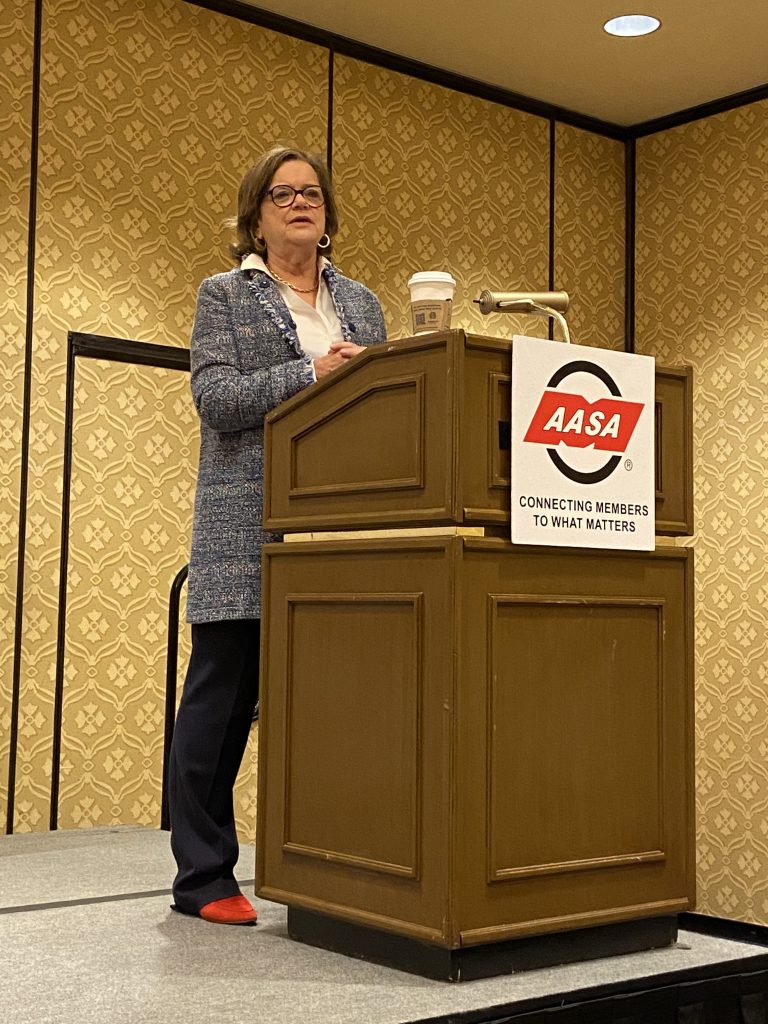

“2023 and 2024, I believe, are our years to get this done,” said Ann Wilson, senior vice president of government affairs at the Motor & Equipment Manufacturers Association (MEMA), under which aftermarket suppliers are represented by the Automotive Aftermarket Suppliers Association (AASA).

“My concern is, if we don’t get it done in the next Congress, we’re going to miss our best chance. That doesn’t mean that we’ll never be able to address it. But we are going to miss our best chance.”

A right to repair bill was introduced in Canada earlier this year. Brian Masse, an NDP member of Parliament representing Windsor West in Ontario, introduced legislation as a private member’s bill.

In the U.S., Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL), chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Energy, introduced the Right to Equitable and Professional Auto Industry Repair (REPAIR) Act — one of three right to repair bills that would impact the automotive, agriculture and electronics industries.

Right to repair is “a global issue,” noted Paul McCarthy, president and CEO of AASA at the group’s Global Summit in Florida earlier this year.

He noted that other countries are looking to the U.S. to lead the way in establishing legislation that they can essentially use as a precedent.

“So we’re fighting for it here in the U.S., [but] just know we’re fighting for it on a global basis on behalf of our global industry,” he said. “They’re looking to us for that leadership.”

And legislation appears to be the way this issue will be settled. In fact, it’s the preferred option, according to Alana Baker, senior director of government relations with the Automotive Industries Association of Canada.

There are a few legal battles around right to repair going on in the U.S. right now, most notably in Massachusetts where automakers filed a lawsuit challenging the state’s right to repair law which followed state voters approving expanded right to repair laws. A decision around this has been delayed repeatedly this year. There’s also a voter referendum going on in Maine. Meanwhile, 27 different states have some kind of repair access legislation, generally centred around consumer products like cell phones and appliances.

“But the moment that conversation starts at the state level, we are there with our coalition partners to remind them that it also impacts that vehicle that sits in everyone’s garages, driveways, backyard, wherever else they have their vehicles parked,” Wilson said during a media conference at AAPEX 2022. “And I think that’s important because what we see is a growing awareness of elected officials at the state level, at the federal level, that this is an important consumer issue.”

All of this points to a groundswell of support for the right to repair movement. It’s top of peoples’ minds right now and it’s best to strike while the iron is hot to make sure auto is part of the discussion.

“If Congress moves a piece of legislation on [right to repair on other consumer products] and it doesn’t include autos, we’re going to have a harder time catching up with that issue,” Wilson advised. “So this is the time for us to act. This is the time for us to get this done.”

But it’s not all over if it doesn’t get passed soon enough. As Wilson pointed out, the U.S. bill is bi-partisan, which means it has the support of both sides of the political spectrum.

“I do think we have to keep this at the level of ‘Let’s talk about what this means for the single mom in 10 years who can’t get her car fixed with a family … who’s on a budget, trying to figure out how they keep that 12-, 13-year-old car going for school and work and everything like that,’” Wilson said. “And there is not an elected member of Congress, not one single one, who is going to not be worried about that.”

Leave a Reply